Areas blanketed in snow in the latter half of April offer serene settings for summer picnics today, highlighting the pressing need for urban environments to rapidly adapt to changing conditions.

Extreme weather events, becoming increasingly more common due to climate change, pose escalating challenges for cities like Tallinn. Urban vegetation and stormwater management systems that mimic natural processes are emerging as essential tools for responding to weather change and improving urban livability.

It doesn’t necessarily take high-tech solutions, but rather a thoughtful and strategic approach, to embrace nature’s designs. Trees provide shade on hot days, buffer winds during gusty weather and help absorb rainfall. They all contribute to a more resilient urban environment – if you let them.

The Tallinn Green Space Action Plan (2013-2025) asserts that in addition to the positive impact of green spaces on citizens’ health and quality of life, research has demonstrated that vegetation also increases property values and expedites property transactions. Consequently, the soil flourishes for commercial activities, thereby increasing the overall value of the city. The plan affirms the necessity of employing new and innovative methods in the design and maintenance of urban green spaces.

The plan affirms the necessity of employing new and innovative methods in the design and maintenance of urban green spaces. 1

There is still room for flexibility in support of innovation

“I hope that greenery doesn’t only become important when it’s no longer there,” said Kristiina Kupper, a landscape architect for the city of Tallinn, in an interview a few years ago. 2

Although greenery is increasingly valued in Tallinn, outdated regulations and weak rainwater drainage systems continue to hamper progress.

For example, as part of the planning process for a new development, there is always a decision regarding the percentage of the area that needs to be landscaped and the portion of this that should be covered with trees. A common requirement is that 30% of the site must be landscaped, with two-thirds of this being trees (where the canopies of adult trees will eventually cover two-thirds of the landscaped area).

The logical train of thought would be that parking spaces take up a lot of valuable green space on the ground, it would be better to move the cars to an underground garage and create a green space from the roof of the garage, but unfortunately today it is not classified as a green space – even if there is a metre-long layer of soil covered with trees and bushes. Cables and water pipes must not be laid near trees, although electric cables and water pipes can be inside a protective sleeve, so they do not affect the growth of trees and are protected themselves.

In line with this, current landscaping regulations do not include green roofs and facades or container landscaping as part of this green percentage. However, they do provide all the same benefits as ‘normal vegetation’ – reducing heat island effect, providing habitat for birds and small animals, purifying air and reducing noise.

Ultimately, land is a finite resource and a more strategic approach than simply playing with percentages of buildings, roads, garages and landscaping is required to have a modern house – with amenities such as toilets and electricity – and plenty of greenery. To avoid ending up with an area that lacks coherence, it is important to consider the whole landscape when determining the greening of a plot.

Urban spaces with lots of greenery are very attractive, while the rules for achieving this target should be more flexible and in line with today’s best practices.

Rainwater pipes alone are insufficient

Landscaping plays a key role in stormwater management. Natural stormwater solutions, designed to mimic natural ecosystems, aim to collect water, slow its flow, maximise infiltration and evaporation into the ground and clean it of pollutants.

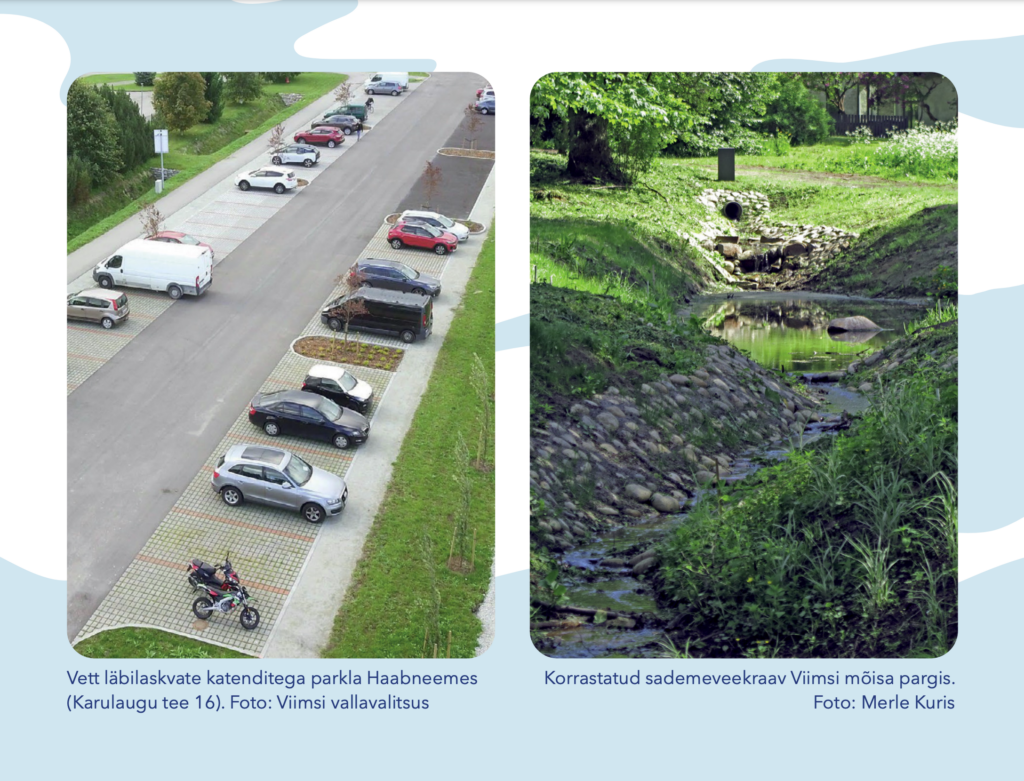

These sustainable stormwater solutions include green roofs, rain gardens, permeable pavements, infiltration strips, slopes and more.

Currently, many areas of Tallinn rely on combined sewers, where sewage and rainwater flow together in a single pipe. However, during heavy rainfall, these pipes can become overwhelmed, leading to problems with water flow and treatment. To deal with this, Tallinn uses emergency discharges, where untreated water is released directly into the sea. In order to avoid overloading the pipes during heavy rainfall events, it’s imperative to research effective stormwater management solutions.

The LIFE UrbanStorm project has recently focused on identifying natural rainwater solutions suitable for Estonian conditions. Test sites in Tallinn and Viimsi have demonstrated the effectiveness of these solutions and highlighted the inadequacy of current systems. 3

The research confirmed that the capacity of today’s systems is already inadequate and will become even more so in the future.

Rather than costly pipeline extensions, the research suggests that natural solutions should be prioritised, as they are often more affordable and contribute to the preservation of biodiversity, surface and groundwater quality and overall environmental well-being.4

Implementing such systems requires a fresh look at existing regulations.

For example, while in Estonia it is common to use of curbstones to raise grass above street level, other countries use landscaping and rain gardens to collect, retain and absorb rainwater from streets. This way the streets become quickly dry after rainfall and the water can be used up to water the greenery.

Collaboration between city regulators, planners and developers is essential to developing smart stormwater solutions – it requires the guidance of experts, including climatologists.

Practical rainwater solutions

In the centre of Antwerp, Belgium, a huge parking lot has been transformed into a 7-hectare park. This brings more than one and a half football fields of greenery to the city centre, including nearly 500 trees. In addition to infiltration, the Zuidpark is lined with rainwater beds. When the car park was moved underground, two rainwater reservoirs were built, which can hold 1.5 million litres of water. 5

In the Danish town of Roskilde, architects Nordarch Rabalder Parken have designed a park that is a great place for recreation, but also provides important flood protection. There is a skate park, trampolines, barbecue-grills, a training area and a stage for cultural events, connected to an intelligent, disaster-proof drainage system that protects the area from annual flooding. In the event of flooding, for example, a skating pool can hold the equivalent of 10 Olympic swimming pools of rainwater. 6

In Gothenburg, Sweden, where it rains 40% of the time, the Rain Gothenburg project decided to get creative with rainwater. One of the solutions created is called Regnlekplatsen, a rainwater play area for children. The area has been designed with special hollows for puddles, channels that create fun swirls of rain and a sandbox where you can build pools, dams and channels. This is the kind of approach the city has in mind for building schools and other developments – water as an asset that can do great things. 7

In conclusion, embracing greenery and implementing sustainable stormwater solutions is an opportunity to create vibrant, resilient and liveable cities. By incorporating nature-inspired designs into urban landscapes, cities like Tallinn can better adapt to changing climates while improving the well-being of residents and the environment.

- Tallinna haljastu tegevuskava aastateks 2013-2025. ↩︎ ↩︎

- Karro-Kalberg, M. Linnahaljastus ei ole vaid garneering, Sirp (2017). ↩︎

- LIFE UrbanStorm. ↩︎

- Mandre, G.,Kuusemets, V.,Kuris, M. Eesti kliimasse sobivate säästvate sademeveelahenduste käsiraamat (2022). ↩︎

- Van parkeerplein naar veelzijdig park (From parking lot to a versatile park). ↩︎

- The Index Project. Rabalder Parken. ↩︎

- Orange, R. Wetter the better: Gothenburg’s bold plan to be world’s best rainy city, The Guardian (2021). ↩︎