This piece doesn’t pamper drivers, but neither does it sit comfortably in a cargo bike. If anything, it’s walking – through the storm – and analyzing where and how to move forward.

[Hundipea CEO Markus Hääl’s opinion essay first published on 3 November 2024 in Delfi Roheportaal]

“Car freedom – does it mean the freedom to drive a car or the freedom to live without one?” Let me start with what bothers me the most: the careless pursuit of political agendas and the media’s click-driven frenzy, fueling polarization. This reduces the complex and systemic issue into a simplistic, black-and-white narrative.

My daily commute involves an equal mix of driving, cycling, scootering, and walking. Buses and trams, however, don’t make it into my routine. Still, I am sharing what we’ve learned and experienced at Hundipea. For years, we’ve engaged with experts and conducted research-based analysis to understand what influences mobility and how mobility, in turn, influences us.

Below is a brief overview of some key, but not all, factors to consider when making systemic changes. Over the next few months, we plan to delve deeper into each of these topics.

Not Convenience, But Luxury

Living downtown is expensive, and a new apartment on the outskirts seems much cheaper—this is often how people reason. However, when we look deeper into the numbers, a different picture emerges. Living on the city’s edge likely requires a car, with an average car lease costing around 500 euros 1. Add fuel, insurance, maintenance, and parking, and that money could alternatively secure a 140,000-euro mortgage – just by ditching the car. And that’s with only one car in the family; if there’s more driving or longer commutes, you’ll likely need a second car, which adds another 250 euros in costs, making the financial burden even heavier. City living may seem like a luxury, but in the long run, living farther out is more expensive for everyone – including the city, which has to maintain roads and public transportation, create school spaces in surrounding municipalities, and more. Poor mobility, air pollution, and noise also degrade the quality of life and significantly raise healthcare costs. 2

Living in a country where public transport cannot realistically reach everywhere with good frequency, it’s inevitable that a car is necessary outside urban areas. In winter, I can get from the countryside in Käsmu to the city in a reasonable time only on Sundays, as it is the only day when the bus currently runs.

Mobility Equality

If I live near the city center and head downtown to work, I’ll likely take my car because it’s the fastest option. Meanwhile, my colleague, who lives further out, is stuck in traffic behind me, also choosing the fastest option available to her. I might prefer using an alternative form of transport because the distance is short, but there isn’t yet an equally efficient alternative. My colleague also wants to get to work quickly, but I’m part of the traffic that’s holding her back.

If I, as a city center resident, preferred another mode of transportation, my colleague coming from the outskirts would arrive faster and with smoother traffic flow. This is just one example of how mobility is a system where everything is interconnected.

It’s clear and proven: the more diverse and equitable the transportation options, the cheaper and smoother traffic is for everyone. Equal access to various modes of transport reduces congestion and improves overall mobility efficiency. When people in or near the city center have alternatives to driving—such as walking, biking, or taking the tram—there’s less car traffic in the city center. This, in turn, reduces congestion for everyone, including for those who travel from further away and have no choice but to drive, as many former car users are now moving through the city via other means. But these alternatives must be faster, more convenient, and more efficient to compete with private cars.

Investments in cycling paths and public transport infrastructure significantly reduce car traffic and improve overall quality of life.3 In New York, a consistent effort to build bike lanes over the past few decades has improved traffic flow and reduced accidents.4 A large-scale study in Paris tracked the movement patterns of over 3,000 residents using GPS for six months. The study found that 44% of trips were made on foot, 34% by public transport, 11% by bike, and only 9% by car .5

If large cities, both in population and size, can succeed with these changes and prove that quality of life improves this way, we in Estonia should be able to move even faster. Our neighbor Helsinki has been investing in an efficient public transport system and cycling infrastructure for years. Thanks to this, nearly 60% of residents use public transport for daily commuting, and cycling has also seen significant growth in recent years.

According to data from the Green Tiger transport roadmap published earlier this year, over half of urban workers in Estonia commute by car, while only one in ten uses public transport, and about 3% cycle to work. However, the latter figure has doubled in the past two years.

Mobility planning that ensures equal access to transport modes (safe walking and cycling paths, convenient public transport, and necessary local services) reduces social and economic inequality, improves quality of life, and promotes sustainable development. Young people, in particular, are moving towards more diverse and environmentally friendly ways of getting around, with less interest in owning cars. 6

Mixed-use and Polycentrism

We’ve all been stuck in a frustrating traffic jam, staring wistfully at the empty lane heading in the opposite direction – wishing that we were going that way instead, with no delays. This happens when the city follows a typical pattern of commuting from home to work in the city center and back again in the evening. But if services were more accessible around residential areas, there would be fewer one-way traffic jams, and the roads would be used more efficiently.

A mixed-use and polycentric city (as opposed to monofunctional and monocentric) means that various centers – stores, offices, homes, daycares, schools, and health centers – are spread throughout the city rather than concentrated in specific areas. The more functioning centers with different functions, the less need there is for mass commuting at specific times, clogging the roads with cars.

This reduces the need for people to commute en masse, inching through morning and evening traffic between city center jobs and schools, and suburban homes and shops. When a grocery store is close to home, you can pop by on the way home from work, maybe even while walking or biking. When a child’s school is accessible via safe bike paths, they can ride their bike independently without needing a car ride from a parent. As people go about their daily activities at various times of day, traffic jams lessen because not everyone is trying to get from one place to another by car at the same time.

A functioning city supports people’s health. Walking and cycling as part of daily life reduce health risks and improve quality of life (WHO). In the UK, it has been proven that cycling helps reduce anxiety and depression.7 A large-scale study across seven European cities confirmed that over half of the cyclists felt that cycling improved their mood, and in Germany, researchers showed that expanding bike lanes significantly reduced obesity and diabetes.8

Mobility Choices Are Driven by Time

Time always seems in short supply – we juggle work, sleep, and personal time within the day’s limits. The time spent moving from one place or activity to another is inevitably taken from our personal time. So, when choosing between different modes of transport, we opt for the fastest one. It is the city’s responsibility to manage and provide different transportation options.

If public transport moves faster than a car, it immediately becomes the more convenient and efficient option for getting around the city, reducing the number of cars and freeing up space for those who genuinely need to drive.

Studies show that in cities where public transport is convenient, people prefer it .9

The capacity of the transport system improves directly. Imagine 60 people, each driving separately – that’s 60 cars. If they cycle, they take up much less space. If those 60 people take the bus, only one bus is needed. This kind of mode shift greatly improves traffic speed and efficiency.

In turn, the less need city center residents have for a car, the more space there is for people, nature, and recreational areas.

Space and Its Functions

By education, I’m an engineer. This background has provided valuable experience in production efficiency and space planning. I’ve learned the importance of monitoring space utilization in sync with evolving technologies and needs, and the value of boldly reassessing it when necessary – a critical part of operating with purpose. I think we’ve reached this point with the corridors designed for mobility in our urban space. To create general well-being, we should take a moment to reassess how space is used and rethink it. In the long run, this will help us all enjoy a better life.

Estonia’s transport sector has set a goal to reduce emissions by nearly a third by 2035, in line with the European Union’s climate neutrality strategy. This goal can only be achieved by improving mobility, enhancing its efficiency, and supporting sustainable mobility principles. 10

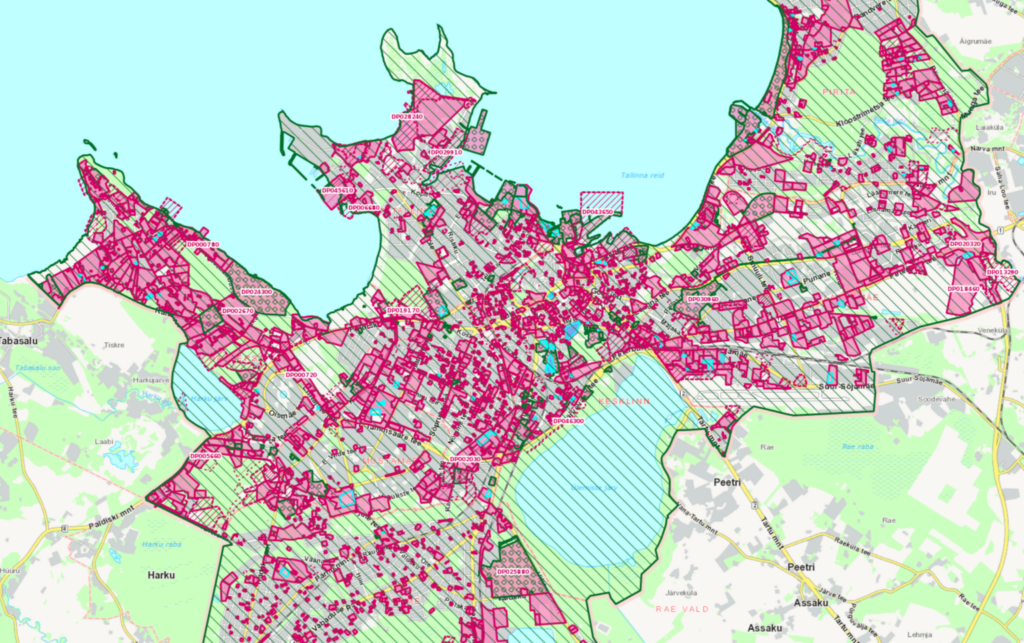

As the diversity of transport options improves, daily car traffic decreases. This opens up an opportunity to rethink street space and make it more pleasant for everyone. For example, parking spaces could be converted into bike racks, playgrounds, pocket parks, or wider sidewalks. Most roads and streets in Tallinn are already owned by the city, creating a solid foundation for street space decision-making.

People with limited mobility must be able to park right at street level by the door – that’s clear. But if parking spots were reserved only for those who truly need them, and the rest of the cars parked in garages, significantly more space would be available for people, nature, outdoor cafes, and other enjoyable uses.

This way, we create a more pleasant city, and at the same time, we contribute to climate action without the need for extreme spending. Everyone has their own perspective, but at the end of the day, whether in a car, a cargo bike, or walking hand-in-hand, children need to arrive safely at kindergarten. There, while playing in the sandbox or building blocks, they’re already shaping future urban innovations – hopefully dreaming of flying unicorns and dragons, not just a pleasant and safe route home, which really shouldn’t be the stuff of fantasy.

- Autoliisingu populaarsustabelit juhib endiselt Toyota. Delfi Ärileht. 23.08.2024. URL. ↩︎

- Promoting cycling can save lives and advance health across Europe through improved air quality and increased physical activity. World Health Organisation. 03.06.2021. URL. ↩︎

- Rajé, Fiona, Saffrey, Andrew. The Value of Cycling. 2016. URL. ↩︎

- Gu J, Mohit B, Muennig PA. The cost-effectiveness of bike lanes in New York City. Inj Prev. 2017. URL. ↩︎

- Sage, Adam. Cyclists overtake cars in Paris. The Times. 15.04.2024. URL. ↩︎

- Arenguseire Keskus. Liikuvuse tulevik. Arengusuundumused aastani 2035. Kokkuvõte. 2021. URL. ↩︎

- Transport for London. New TfL data shows sustained increases in walking and cycling in the capital. 06.12.2023. URL. ↩︎

- Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal). Cycling is the urban transport mode associated with the greatest health benefits. 13.08.2028. URL. ↩︎

- Göransson, J., Andersson, H. Factors that make public transport systems attractive: a review of travel preferences and travel mode choices. 2023. URL. ↩︎

- Arenguseire Keskus. Liikuvuse tulevik. Arengusuundumused aastani 2035. Kokkuvõte. 2021. URL. ↩︎