Vana-Kalamaja street (Photo: Tõnu Tunnel)

“Every trip begins and ends with walking, and therefore everyone is a pedestrian on a city’s street at some point. Providing continuous and unobstructed clear paths ensures walkable neighborhoods for everyone. Street designs should always prioritize safe facilities for pedestrians, and measure their success from the pedestrian perspective. A walkable city that is easy and safe to navigate offers a level of independence and equity to its citizens.” (Global Street Design Guide)

Architect and urban planner Darina Nossova points out that although these ideas sound self-evident, they are often forgotten in practice. “If the pedestrian through zone is fragmented, filled with obstacles or illogical solutions, the whole function of the street is disrupted,” she explains. “A continuous, clear path is the bloodstream of urban space, bringing life to every part of it. When it is blocked, the surrounding area stagnates as well.”

Darina notes that some streets in Tallinn already show that better design is possible. “Take Vana-Kalamaja or the section of J. Poska Street. Even the recently renovated stretch of Gonsiori Street gives more space to pedestrians. Of course, they can be criticised, but compared to much of Tallinn’s urban environment, walking there feels noticeably more comfortable.”

What does a continuous, clear path mean?

A continuous, clear path is more than just a smooth sidewalk. It is an accessible pedestrian through zone with clear sightlines, free of steps, narrow pinch points, or misplaced furnishings. “For someone with a wheelchair or stroller, a trash bin in the middle of the path can be just as much of a barrier as a high curb,” Darina explains.

“Each sidewalk’s clear path should be complemented with active street edges and accessible facilities to make the journey comfortable and engaging. Cities are places for people, and they use streets not only for walking but also for resting, sitting, playing, and waiting. This requires making people the highest priority in street design, with careful consideration for the most vulnerable users: the young, the elderly, and those with diminished perceptual or mobility abilities.” (Global Street Design Guide)

Darina sums it up: “In practice, this means there must be no barriers that a running child or elderly person could trip over, nor obstacles that make movement with a stroller or wheelchair impossible. If we design for the most vulnerable, the environment becomes safe and comfortable for everyone. And it also means that street furniture does not belong in the pedestrian through zone, it must always have its own designated space.”

Street zones: logic and creativity

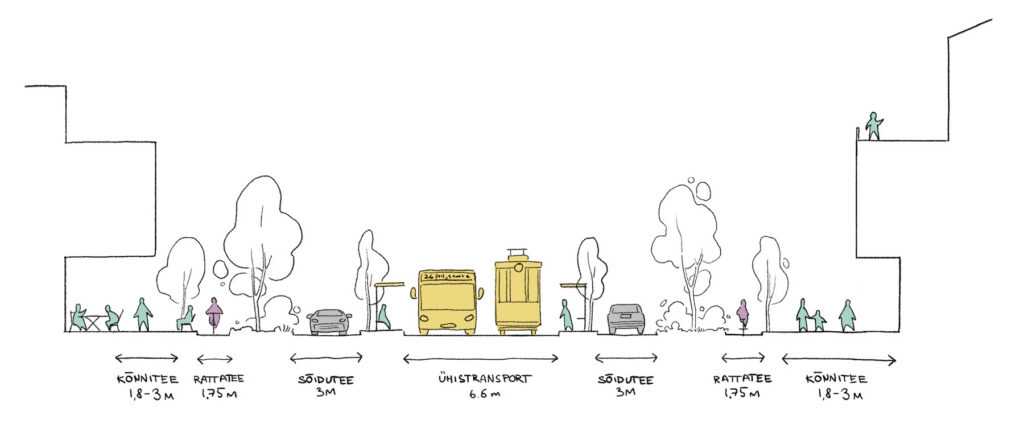

At Hundipea, the minimum sidewalk width is set at 1.8 meters, enough for two people in wheelchairs to pass each other comfortably. On quiet residential streets, the goal is over 2 meters, on active shopping streets at least 2.4 meters, and in the city center, 3 meters or more. Adequate width is a prerequisite for people to feel comfortable as they move.

But sidewalks are only part of the picture. Streets also need well-defined zones.

“The furnishing zone is a creative part of the street, usually running parallel to the sidewalk. The placement of posts, benches, or planters may seem like a detail, but it often determines whether a space feels safe and logical,” Darina explains. At Hundipea, we plan to create dedicated furnishing zones that keep pedestrian paths clear while giving designers room for creativity.

This zone can host greenery, trees, benches, bins, lighting, bike racks, or even rain gardens that collect and filter stormwater. “It is the place to experiment, to bring in green, to create little pockets that make the street unique. There are fewer strict rules here, and landscape architects have greater freedom,” Darina says.

She points to Antwerp’s Lange Koepoortstraat as a strong example: “It is a small, charming shopping street that was redesigned so the central space is shared between pedestrians and the few vehicles that enter. Cars move very slowly there precisely because of the design. The furnishing and planting zones are well done, separating the shared space from the pedestrian zone. The street’s strength lies in the character of its small local businesses, which make the place lively and welcoming.” After the redesign, businesses were able to extend their activities outdoors, and many began to thrive thanks to the pleasant public environment.

In Auckland, New Zealand, Jellicoe Street is another good example. Although not a shared street, it shows how a well-designed furnishing zone can calm traffic and create a safe and inviting atmosphere for pedestrians.

Too often, however, we see the opposite: posts and benches placed directly in the middle of sidewalks, leaving too little space and creating dangerous situations for people with visual impairments. At Hundipea, we will follow a clear zone logic where each function has its own place, so the pedestrian through zone remains unobstructed.

Buffers and frontage zones

Where sidewalks border busy bike lanes or car lanes, furnishing zones alone are not enough. Pedestrians need a protective buffer. “The denser and faster the traffic, the more important the buffer,” Darina stresses. Trees and shrubs absorb noise at different heights, filter dust, and create safer, more human-scaled spaces.

International examples include Vilnius’s Pylimo Street and Poznań’s recently renovated central streets such as Plac Wolności and Święty Marcin, where greenery has been added to protect pedestrians and cyclists from noise and dust while also making the streets visually attractive.

Another important element is the frontage zone, the strip directly in front of buildings. This is where cafés, shops, and services can extend with a counter, terrace, or outdoor seating. Even a 1-4 meter frontage adds life to the street and makes it more welcoming.

Crossing the street is part of the journey

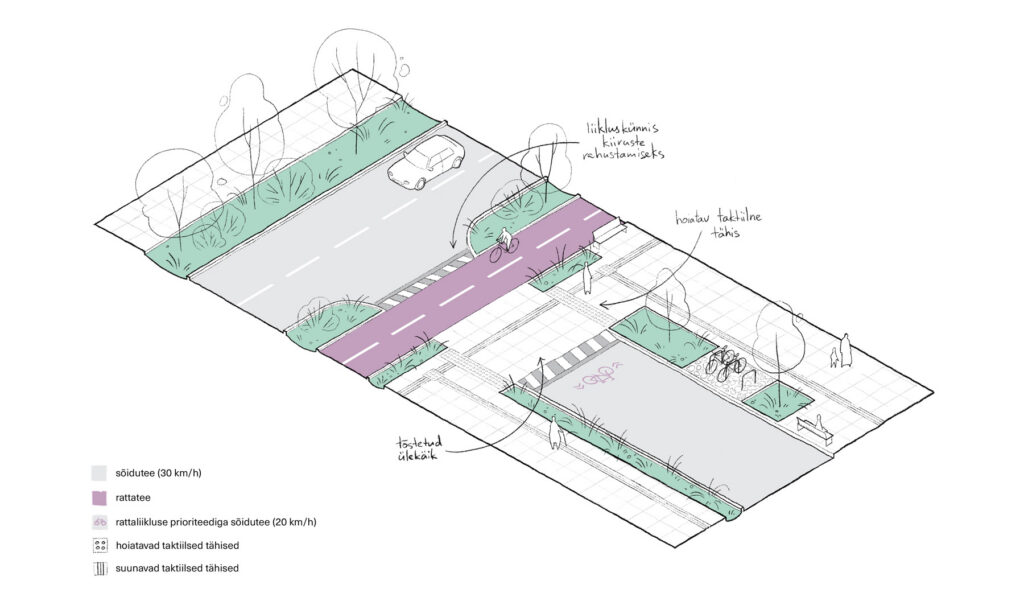

Crossings are not just interruptions, they are part of the pedestrian’s continuous path. Traditional zebra crossings work on high-traffic streets, but they must be designed with accessibility in mind: dropped curbs, gentle slopes (ideal 1:12, max 1:10), slip-resistant surfaces, and widths matching the sidewalks.

In calmer areas, raised crosswalks, where the road surface is lifted to sidewalk level, are safer and more intuitive. “They make pedestrian priority visible, calm drivers immediately, and strengthen the sense of continuity,” Darina explains.

Raised crosswalks work especially well where car speeds are lower and pedestrian volumes are higher, such as residential or shopping streets. Properly planned, they also act as calming gateways when turning from a bigger street into a smaller one.

Pedestrian streets

Some streets are designed for pedestrians only. “These are the lifelines of residential neighborhoods. Here children play, neighbors meet, and people arrive home not via the main arterial but through the back street,” Darina notes.

International experience shows that pedestrianization is not a death sentence for businesses. Quite the opposite: Copenhagen’s first experiments proved that cafés and shops thrived once cars were removed. The same is true today on Tallinn’s Vana-Kalamaja Street.

Key here is width, at least 3.5 meters, so that service and emergency vehicles can still enter if needed, while leaving room for outdoor businesses and community life.

Paving materials matter

Street surface materials are not just about aesthetics, they communicate function. “Paving materials tell the user where they are and how to use the space,” Darina explains. Asphalt changing to paving stones signals to a driver that they have entered a calmer zone. Larger paving slabs on a sidewalk suggest a transition into a square or promenade. For people with impaired vision, textures are critical navigation aids. Surfaces must be solid, non-slippery, and not overly reflective.

In conclusion: measuring success by the pedestrian

Hundipea’s street design is not about looks, it is about creating a functioning everyday life. Clear pedestrian through zones, well-placed furnishing, protective buffers, and active first floors all matter to ensure walking feels safe, comfortable, and pleasant.

“If the most vulnerable, children, the elderly, people with disabilities, feel free and confident, then the street works for everyone,” Darina emphasizes.

“All these rules are important, but they are not enough. A place must also feel alive and inviting. If streets are technically accessible but the neighborhood is empty, full of speculative real estate and overpriced restaurants that no one uses during the day, the result is still a lifeless and unpleasant street.”

That is why street design cannot be judged only by dimensions and standards. The real test is how people feel there. Streets must also provide for drivers and cyclists, but the heartbeat of the city, and the true measure of quality, is how well we design for those who walk.

Read the first article of the series “Human-centred streets”