Streets aren’t just paved space between buildings – they’re part of the living environment, shaping how we move and how we feel. Our daily journeys often begin at the edge of the neighbourhood. If we want streets to feel like an extension of home, we have to ask: how are they created, and for whom? Architect and urban planner Darina Nossova shares the principles behind street design at Hundipea.

Who are the streets for?

“When we talk about street users, the image is often a driver or an office worker,” says Darina. “But the reality is far more diverse – children, elderly, people with mobility or visual impairments, parents with strollers, someone with a broken leg… We need to design with the full range of human needs in mind.”

Even small design details can make a difference. In a previous conversation, Maikel Mõttus from the Estonian Chamber of Disabled People pointed out how a high curb, a heavy door, or a locked public toilet can limit access. “The job of street design is to remove those barriers,” Darina adds.

She outlines some of the users and needs to consider:

- Wheelchair users and people with mobility aids who need gentle slopes and wide pathways.

- People with visual impairments who rely on tactile cues, like textured tiles near stairs or crossings.

- People with hearing loss benefit from visual contrast and clear signage.

- Children and older adults who need safe crossings, slower traffic, and space to rest.

- Parents with strollers and people with mobility issues, who need step-free access and reliable connections to public transport.

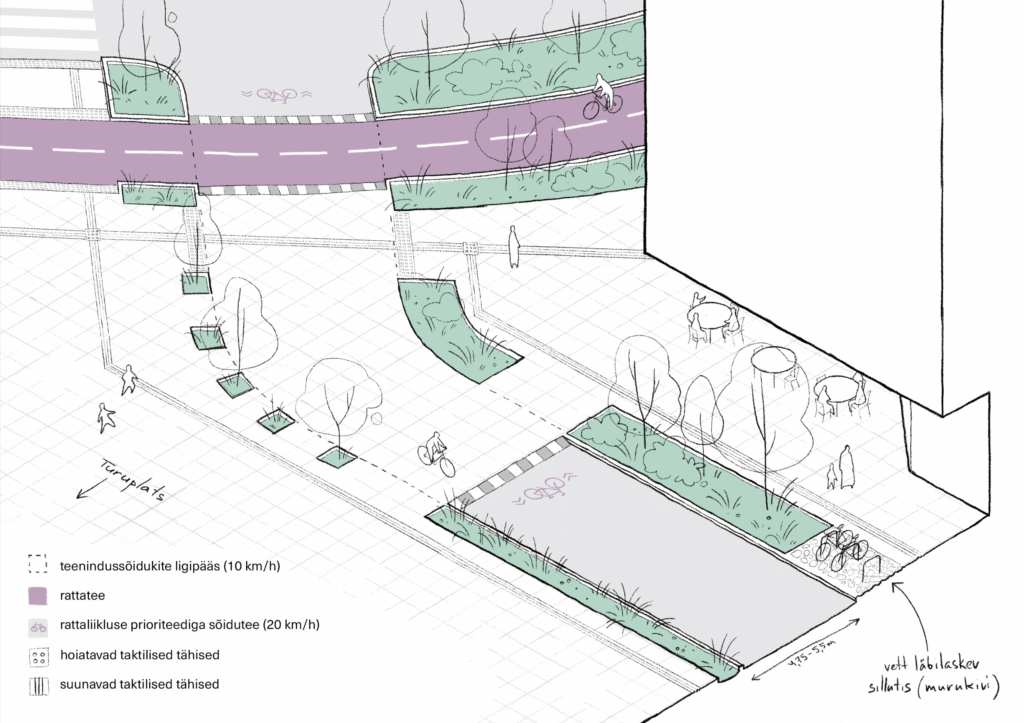

- People on bikes who need a clear, connected network: wide lanes in both directions or shared low-traffic streets.

- Dog walkers, skaters, scooter riders, runners, and walkers, all with different speeds and needs.

- Public transport which requires dedicated lanes.

- Cars, which still need space, but not at the expense of everyone else.

Designing for freedom of movement

“Getting from A to B isn’t just about transport,” says Darina. “It’s a chain where every link – people, mode of movement, and reason for travel – matters. Our job is to make sure nothing breaks that chain.”

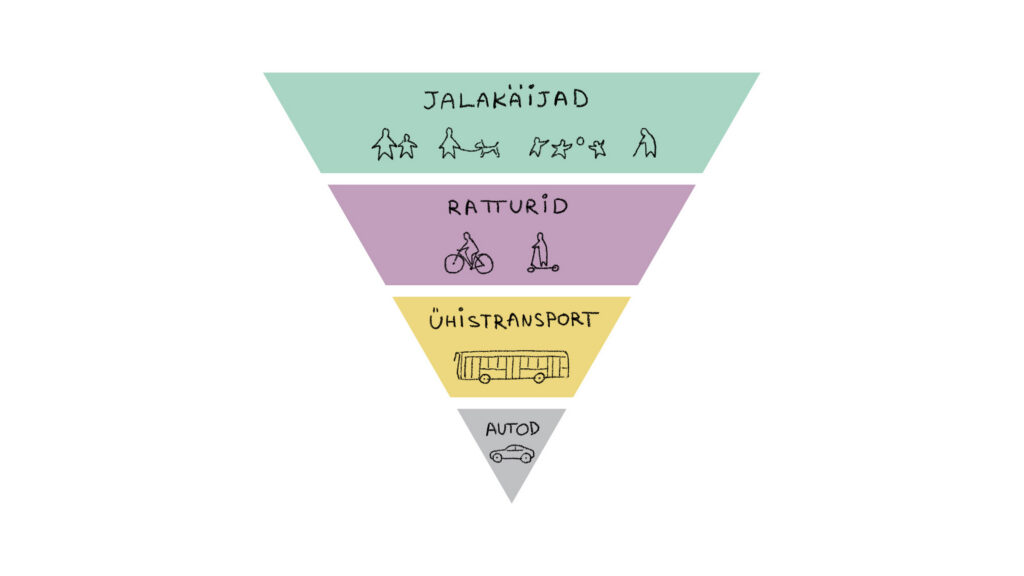

Hundipea follows a mobility hierarchy: pedestrians first, then cyclists, then public transport, and only after that, cars.

“That doesn’t mean cars are excluded,” she notes. “But planning has to start from the human scale, not the vehicle scale.”

Often, space for cars is overestimated: “You’ll see oversized lanes, wide intersections, turning pockets that aren’t actually needed. These encourage higher speeds and make streets less safe and inviting.”

For other users to feel safe – pedestrians, cyclists, parents with strollers – car space must be used carefully, with narrower lanes and smaller turning radius. “You can calm traffic through design: S-curves, raised crossings, or cobbled areas work better than just speed limit signs.”

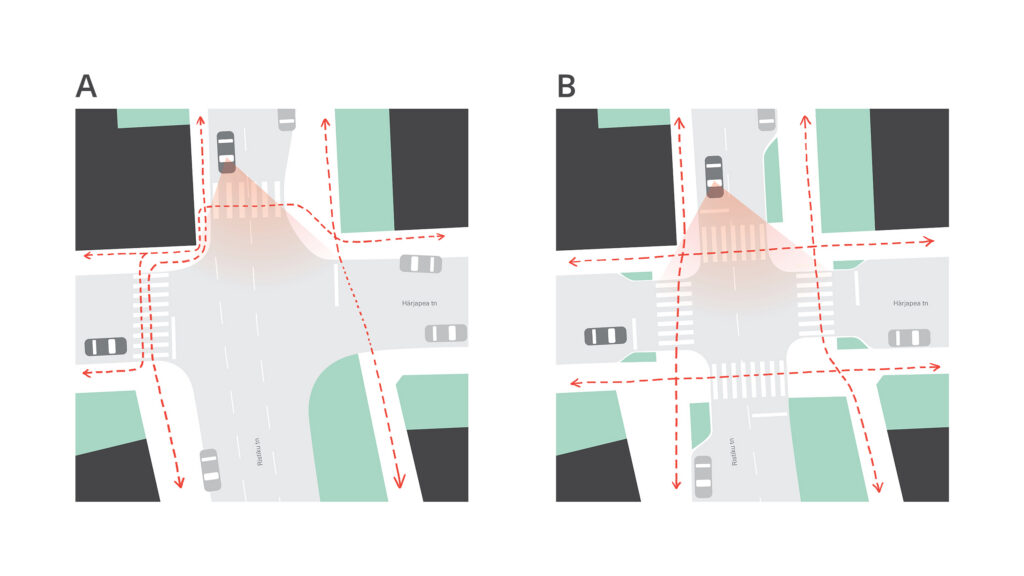

Darina offers a concrete example from the Ristiku–Härjapea intersection (A – current situation, B – possible improvement):

“On the suggested solution, we reduced the corner radius to 1.5 metres. This allowed us to move the crosswalks closer to the intersection, making the junction more compact. The result: it’s more convenient for pedestrians and their routes are more logical. Drivers are forced to slow down when turning. The compact intersection also eliminates a hazardous blind spot – now all crossing points and pedestrians are visible to drivers.”

As with other things at Hundipea, solutions are tested before being built. “We prototype ideas before rolling them out. That lets us see what works and adjust as needed,” Darina explains. “We also invite citizens and professionals to give feedback. Every street will have a role in the bigger picture, whether that’s a promenade, a quiet residential lane, or a main connection route.”

In an upcoming post, we’ll talk more about what makes a good sidewalk.

Designing the full picture

Hundipea’s scale and long time horizon make it possible to design the whole 41-hectare area as a whole, not plan just streets or plots. It’s also an opportunity to test, learn, and improve along the way.

“We follow the 15-minute city principle: everything for daily life – parks, schools, playgrounds, grocery stores, public transport – should be easily reachable on foot or by bike. If people can move logically, pause, rest, and enjoy their surroundings, they’ll feel a sense of ownership and comfort in the space.”

Good urban space doesn’t happen by accident. “The street design has to fit in the overall pattern – something people can intuitively ‘read’ when taking a morning walk, riding a bicycle, or pausing for a break,” Darina says. A well-designed street works for different users and modes of transport, smoothly and without conflict.

Designing for the users

“When we talk about the user, we don’t just mean the pedestrian, cyclist, or parent with a stroller,” says Darina. “We also mean the bird, the tree, the rainwater – everything that moves through or is affected by the urban environment.”

This broader understanding is core to how the streets at Hundipea are designed. “A good street or park is like a good product – it’s designed with intention, tested in real life, and built to support everyday life, natural processes, and living together with other species.”