Tallinn has reinstated the position of City Architect, who will create a proper plan, a strategic approach to urban planning. Previously, the city has been criticized for a lack of strategic vision in its decision-making. While there are many great ideas in Tallinn, the City Architect can provide a much-needed direction and oversight to ensure these plans are effectively implemented. A good tool for this is the structure plan, which I strongly recommend to both the city representatives and the new City Architect.

[Article first published on Edasi.org news site by Hundipea CEO Markus Hääl ]

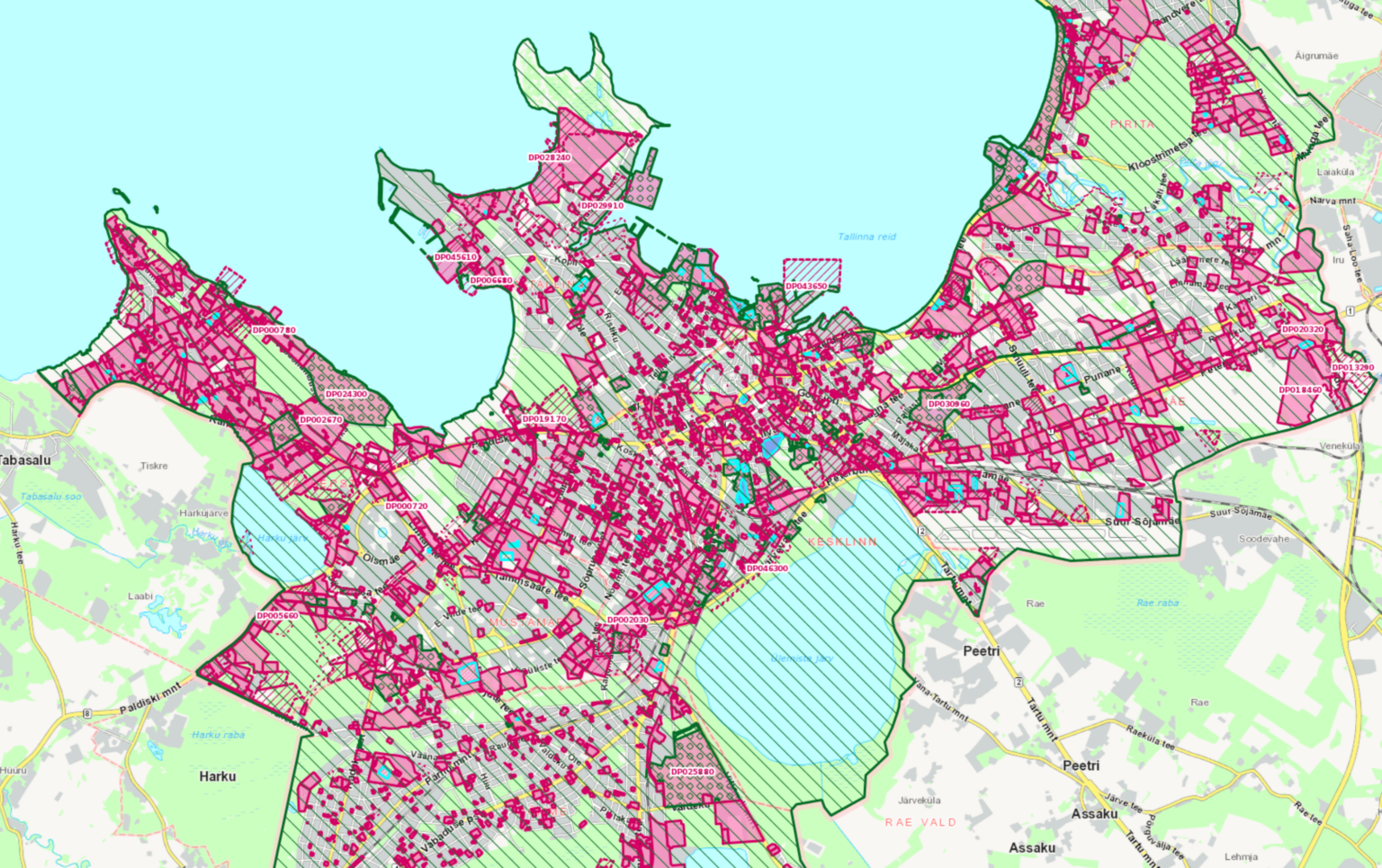

Currently, most of Tallinn’s development occurs on a plot-by-plot basis, where landowners and developers concentrate their efforts on specific areas, prioritizing their own profits, needs, and values. However, the values and solutions of developers of different plots are often conflicting, and there is no shared vision and values for the neighbourhoods.

I have spoken to the architect and town planner Tõnis Arjus, according to him, Tallinn has very good levers at its disposal to distinguish itself from all the other cities in terms of well-thought-out spatial solutions. “This is the only city in Estonia where, in addition to the general procedures prescribed by law, there is also the possibility of drawing up structural plans,” he points out.

The concept of a structure plan has already been introduced into Tallinn’s planning regulations1, it is only a matter of consciously using this potential. It is a planning approach that enables a broader analysis and shaping of the city, focusing on the interrelationships between different regions and managing urban development as a cohesive system.

Cooperation is the key to integral city planning

When I discuss local urban planning with representatives of the Tallinn Strategy Centre, urban planner and architect Paco-Ernest Ulman admits that Tallinn is “a city of half-baked ideas”.

The comprehensive plan (üldplaneering) is a long-term spatial development document for the city that defines the directions and principles of the city’s development. It summarises the city’s vision, sustainable development objectives and policies in a guide form. It is an important tool for planning and shaping the future of the city. A comprehensive plan is usually prepared for a larger area – the whole city or the whole district as a single plan. It is therefore prepared by public authorities, i.e. cities, counties and municipalities.

The comprehensive plan is followed by the detailed plan (detailplaneering), which examines the development conditions of the areas defined in the comprehensive plan and is drawn up by the owner of a specific area of land. This plan is the direct basis for planning and building projects. Thus – the city sets the framework with the comprehensive plan, and the landowner, in turn, fills in the details of this framework with the detailed plan.

Ulman emphasizes that beyond the overarching plan and specific details, it is crucial to consider the spatial dimensions of the city—what kind of space it will become. In the context of urban dynamics, every plot or development has an impact on its surroundings, the street space and the overall quality of the urban space.

The key to understanding, planning and improving the relationship between the city and its different parts, and shaping the mixed-use environment, could be a structural plan. This prioritizes the needs of urban residents and takes into account the values of high quality urban space.

According to Ulman, the term “spatial vision” is more flexible than “structural plan” and less intimidating for landowners, emphasizing the aspect of multidimensionality. Today, moving from one type of plan to another is a big leap, as the contrast in detail is great – whereas the comprehensive plan is a very large and general document, the detailed plan concerns a specific area and goes into detail.

Kaidi Põldoja, Head of the Spatial Planning Department at the Strategy Centre, agrees that there are numerous areas requiring spatial consideration. She describes that in the planning practice it is common that even neighboring plots are not planned to relate to each other spatially in their detailed plans. Põldoja admits that “when it comes to working together, one of the biggest problems the City of Tallinn faces is that officials can tell completely different stories”. The comprehensive plan is too general, she confirms.

A structure plan would be an ideal link between the two types of planning. It would bring all the related parties together at an earlier stage, and the plan would be produced collaboratively. It would also reduce the number of disputes between the city and the landowners, leaving more room for manoeuvre. Ulman also stressed that the structure plan is a working tool – it is constantly in flux, but thanks to it, answers can be given to different parties.

In Estonia, municipalities do not have much land of their own that is suitable for development, so a structure plan would be a good tool for specifying the spatial quality of different locations. I think it would allow the city to show a long-term vision to landowners and justify why solutions have been made the way they have. Since many details can be specified in the structure plan, it would also give the comprehensive plan a little more freedom.

Polycentric city

In a diverse and sustainable urban area, there are several smaller centres in addition to the heart of the city, and the inhabitants of all districts can rely on the local centre in their daily lives: work, shops and leisure activities are always close to home.

This means that forced daily commute is reduced, services are accessible by walking or cycling, and each neighborhood is special and has its own character. In the local centre, you always come into contact with the same people, which also encourages the development of social relationships and the so-called village mentality, which promotes a sense of community and is extremely necessary and useful for people on a social level.

Põldoja believes that Tallinn will develop in the same direction as Oslo, that people value their time much more – nobody wants to spend half an hour getting a carton of milk. For now, there is no other way to get around than to spend precious time driving.

When one thinks of a true polycentric city, one thinks of Copenhagen, Vienna, Amsterdam, Stockholm, Brussels, where there are areas or neighborhoods with distinct identities that have independent economic, cultural or commercial significance. Tallinn is primarily considered a monocentric city, with the Old Town and Town Hall Square as its dominant centre.

If you imagine the different centres of a city, the most logical way to define the centre is as an independently functioning part of the city2. This means that this part of the city has all functions and people live near these functions. Within the framework of the Tallinn 2035 strategy, Tallinn has also begun to map itself as a multi-center city, while the strategy considers shopping malls as centers, such as Nõmme Center, Kristiine Center, and others3.

In order for Tallinn to become a truly polycentric city, an additional link should be created to provide flexibility in the planning process. This will allow the parties to consciously work together on plans to create denser central areas. A truly functioning centre can only be created when the city and landowners sit down together.

Endrik Mänd, an urban planner and former chief architect of the city of Tallinn, has written about why more structure plans could be implemented in Estonia and how there is currently a gap between the two types of planning. According to him, the structure plan is “primarily the urban planning vision of the municipality, which has two main goals: to provide a flexible and up-to-date spatial interpretation of the current comprehensive plan, and to establish a starting point for the preparation of detailed plans that anticipates the vision of those interested in the plan”.

Mänd emphasises that the structural plan focuses less on the usual planning figures and more on the spatial treatment of the quality and identity of the region. He also points out, as a major contradiction, that currently the time taken to draw up plans is the same as the expected time taken to carry out projects, which means that the new plan will probably lose its relevance right from the start4.

So far, structural plans have been drawn up for developments in the Vanasadama area, Sikupilli, Sossi mägi, the Airport-Ülemiste campus, at the Skoone bastion and in the area of the Narva street and Mäe intersection56.

The Danish way

Tõnis Arjus also says that somehow we still want to make all urban planning mistakes ourselves and are unwilling to learn from others – but it would be worth it. “There are many examples, but you only need to look at Copenhagen to find them,” he says, explaining that Copenhagen is also famous for smart urban planning with the so-called Five Finger Plan, which ensured that new settlements are developed along public transport corridors.

As in Estonia, comprehensive plans are the general guideline in Denmark, but master plans, similar to structural plans, are drawn up for key sites. A good example of this is the Nordhavn district in Copenhagen. While general and detailed plans are quite rigid in Estonia – the aim is to find the most appropriate plan for everyone, which requires a lot of planning and consideration – the Nordhavn master plan has flexibility and responsiveness already built into it.

The master plan is also a statement of the district’s main objectives, development directions and overall strategy, but the plan is subject to revision over time. The Danes describe their Nordhavn Masterplan as an ever-changing document – it was drawn up in 2008, thoroughly updated in 2018 and now again in 2023. Such an option offers more flexibility, both in terms of time and content, and makes it easier to put together the agreed plan and to correct and refine it at a later stage. This is something that happens in all building and planning – it is not something to be feared and does not cause additional problems.

In order for Tallinn’s development to be well thought out and at the same time adaptable to changing circumstances, it is important to actively implement all appropriate measures. Speed does not necessarily mean low quality. It means that the right procedures are applied in the right places.

Given the very long timescales involved in preparing comprehensive plans, it is unthinkable to wait for the whole city to be replanned in a rapidly changing world. We must adopt a more proactive approach to ensure that urban spaces reflect contemporary and progressive values for both citizens and visitors.

- Tallinn Planning act. Riigi Teataja. https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/430062020046 ↩︎

- Abozeid, A.S.M., AboElatta, T.A. Polycentric vs monocentric urban structure contribution to national development. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 68, 11 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s44147-021-00011-1

↩︎ - Tallinn 2035 Development Strategy, Tallinn. https://strateegia.tallinn.ee/sobralik-linnaruum/lisa-1-4 ↩︎

- Mänd, E. Ajakiri Maja. Mõtestatud ruumiloome menetluskultuuri virvarris (2023) ↩︎

- Linnaehituslikud visioonid, Tallinn, https://www.tallinn.ee/et/ruumiloome/linnaehituslikud-visioonid ↩︎

- Linnaruumilise arengu ettepanekud, Tallinn.

https://www.tallinn.ee/et/ruumiloome/linnaruumilise-arengu-ettepanekud ↩︎